-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

Exploring The Intricate World Of High Frequency PCB Design And Signal Integrity For Advanced Electronic Applications And High Speed Communications

In the rapidly evolving landscape of modern electronics, the demand for faster data rates, higher bandwidth, and more compact devices has pushed traditional printed circuit board (PCB) design to its limits. This has given rise to the specialized and critical discipline of high-frequency PCB design, a field where the physical realities of electromagnetic theory directly dictate the success or failure of advanced systems. From the smartphones in our pockets and the autonomous vehicles on our roads to the vast data centers powering the cloud and cutting-edge radar systems, the integrity of signals traveling at gigahertz speeds is paramount. "Exploring The Intricate World Of High Frequency PCB Design And Signal Integrity For Advanced Electronic Applications And High Speed Communications" delves into this complex intersection of physics, materials science, and engineering. It is a journey into a world where traces on a board are not mere conductive paths but become transmission lines, where every bend and via can reflect energy, and where the dielectric constant of the substrate material is as crucial as the circuit schematic itself. This exploration is not just an academic exercise; it is the foundational work that enables the next generation of technological innovation, ensuring that the digital pulses representing our data arrive intact, on time, and without corrupting their neighbors.

The Fundamental Shift: From DC to RF and Microwave Mindset

The core challenge in high-frequency design is the departure from the lumped-element model that governs lower-speed digital and analog circuits. At low frequencies, a wire or PCB trace is considered a perfect conductor with negligible resistance, and signals are assumed to be uniform across the entire length of the conductor at any given instant. However, as signal frequencies rise into the hundreds of megahertz and gigahertz range, the wavelength of the signal becomes comparable to or even smaller than the physical dimensions of the board traces. This transition marks the point where the lumped model fails and the distributed model takes over.

In this high-frequency regime, every trace must be treated as a transmission line with characteristic impedance, typically targeted at 50 or 75 ohms for single-ended lines and 100 ohms for differential pairs. Failure to properly terminate these transmission lines in their characteristic impedance leads to signal reflections. These reflections cause ringing, overshoot, and undershoot at the receiver, which can distort the signal eye diagram, increase bit error rates, and ultimately cause system failure. Thus, the designer's primary task shifts from simply connecting points A and B to carefully engineering a controlled-impedance environment where the signal propagates as a clean electromagnetic wave.

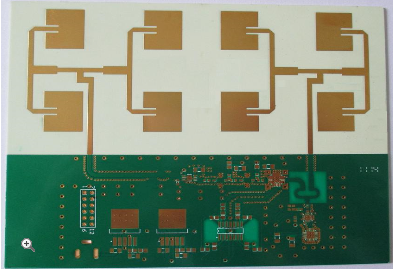

The Critical Role of Materials and Stack-Up

The choice of PCB substrate material is arguably the most significant decision in a high-frequency design. Standard FR-4 material, while cost-effective, exhibits poor performance at high frequencies due to its inconsistent dielectric constant (Dk) and high dissipation factor (Df). The varying Dk leads to impedance variations, while a high Df causes significant signal attenuation, essentially converting precious signal energy into heat. For advanced applications, specialized laminates are essential. Materials like Rogers RO4000 series, Isola's I-Tera, or Taconic's RF products offer tightly controlled and stable Dk values over frequency and temperature, as well as very low loss tangents (Df).

Equally critical is the stack-up design—the arrangement of copper and dielectric layers. A well-planned stack-up ensures proper impedance control for critical signals, provides dedicated ground planes for return paths, and manages crosstalk between layers. It also dictates the manufacturability of microstrip and stripline traces. For instance, embedding a high-speed trace as a stripline between two solid ground planes offers excellent shielding from external noise but can be more challenging to route. A surface microstrip line is easier to access and tune but is more susceptible to external interference. The stack-up is the three-dimensional blueprint that defines the electrical performance of the entire board.

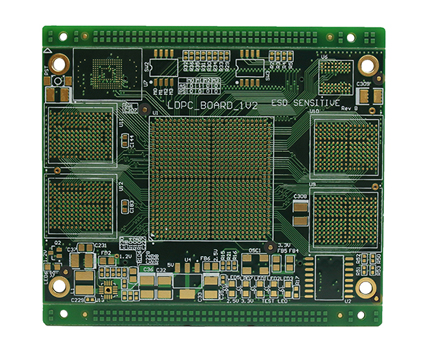

Managing Signal Integrity and Power Integrity

Signal Integrity (SI) is the overarching goal: ensuring signals are received with sufficient fidelity and timing to be correctly interpreted. Key SI challenges include managing reflections through impedance control, minimizing attenuation via low-loss materials and appropriate trace geometry, and suppressing crosstalk. Crosstalk, the unwanted coupling of energy between adjacent traces, is mitigated through careful spacing, the use of ground guards (copper pours connected to ground between sensitive lines), and routing critical differential pairs with tight coupling. Advanced simulation tools are indispensable for predicting and mitigating these effects before fabrication, allowing for virtual prototyping of termination schemes, via transitions, and serpentine delay lines.

Power Integrity (PI) is the inseparable twin of SI. A high-speed digital chip switching billions of times per second demands sudden bursts of current from the power delivery network (PDN). If the PDN has high impedance at the relevant frequencies, it cannot supply this current instantly, leading to a temporary drop in the supply voltage—a phenomenon known as simultaneous switching noise (SSN) or ground bounce. This noise can couple into sensitive signal lines and corrupt data. A robust PDN is built using a combination of bulk capacitors, mid-frequency ceramic capacitors, and a vast array of small, high-frequency decoupling capacitors placed extremely close to the power pins of ICs, all working in concert with low-inductance power and ground planes in the PCB stack-up.

The Imperative of Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)

A board that functions perfectly on the lab bench can still be a commercial failure if it radiates excessive electromagnetic interference (EMI) or is susceptible to external noise. High-frequency designs are potent unintentional radiators; every trace is a potential antenna. Ensuring Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)—that the device does not interfere with others and is not itself interfered with—is a design constraint from the outset. Key strategies include minimizing loop areas for high-current switching circuits, using continuous ground planes to provide shielding and a clean return path, and implementing proper filtering at all cable interfaces (USB, Ethernet, power inputs).

Furthermore, the placement of components and the routing of clocks and other periodic signals are critical for EMC. Sensitive analog sections must be physically isolated from noisy digital sections. Layer transitions for high-speed signals, especially through vias, must be carefully managed to prevent the creation of antenna structures. Often, a combination of simulation for pre-compliance testing and iterative prototyping in a shielded chamber is required to meet stringent regulatory standards like those from the FCC or CE.

Advanced Techniques and Future Frontiers

As data rates push into the realm of 112 Gbps per lane and beyond, even the techniques described above face new challenges. At these extremes, losses become so severe that simple conductor and dielectric losses are no longer the only concerns. Skin effect, which forces current to the surface of a conductor at high frequencies, increases AC resistance. Surface roughness of the copper foil can further exacerbate this loss. To combat this, designers turn to even more advanced materials, low-profile copper foils, and sophisticated modeling that accounts for these roughness effects.

The future of high-speed communication, particularly for intra-data-center and chip-to-chip links, is also driving the adoption of novel technologies co-designed with the PCB. These include photonic integrated circuits, silicon interposers, and the move towards system-in-package (SiP) designs that reduce the distance signals must travel on the traditional PCB. However, the PCB will remain the essential interconnect backbone, evolving to incorporate technologies like embedded actives and passives, and even more exotic materials to support the terabit-era networks of tomorrow. The intricate world of high-frequency PCB design, therefore, remains a dynamic and foundational engineering frontier, continuously adapting to enable the next leap in electronic capability.

REPORT