-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

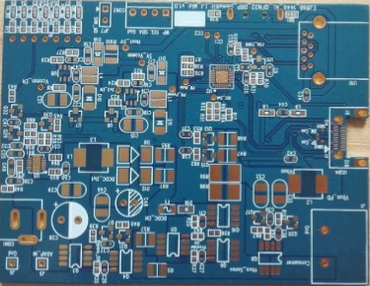

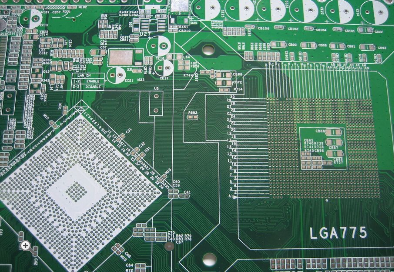

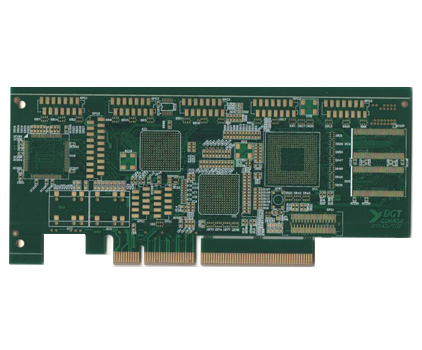

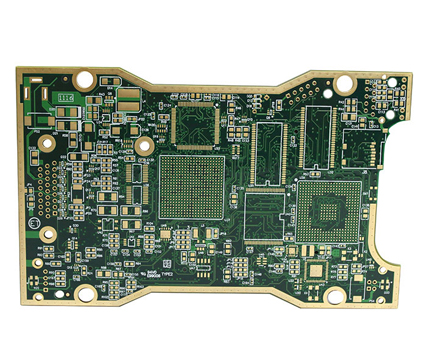

Impact of PCB Trace Geometry on Impedance Exploring Width Spacing and Dielectric Effects for Optimal Circuit Performance

In the realm of modern electronics, where signal integrity is paramount, the design of printed circuit board (PCB) traces transcends mere electrical connectivity. The performance of high-speed digital circuits, RF systems, and sensitive analog applications hinges critically on one fundamental property: controlled impedance. At the heart of achieving this control lies a deep understanding of PCB trace geometry. This article delves into the intricate relationship between trace geometry—specifically width, spacing, and their interaction with the dielectric material—and the resulting characteristic impedance. By exploring these effects, designers can unlock the potential for optimal circuit performance, minimizing signal reflections, crosstalk, and losses that plague high-frequency designs.

The pursuit of controlled impedance is not a mere academic exercise; it is a practical necessity. As clock speeds soar into the gigahertz range and edge rates become ever sharper, PCB traces behave less like simple wires and more like transmission lines. Any mismatch between the trace's characteristic impedance and the impedance of the source and load leads to signal reflections, causing distortion, ringing, and ultimately, data errors. Therefore, precisely engineering the trace's physical dimensions and its environment is essential to ensure clean signal propagation. This exploration provides the foundational knowledge needed to navigate the complex trade-offs in PCB layout, empowering engineers to transform schematic diagrams into reliable, high-performance physical realities.

The Fundamental Role of Trace Width

Trace width is arguably the most direct and influential geometric parameter under a designer's control. Its primary effect on impedance is intuitive: a wider trace presents a larger cross-sectional area for current flow, which decreases the trace's series inductance per unit length. Simultaneously, it increases the parallel capacitance to the reference plane (usually a ground plane). Both of these changes—lower inductance and higher capacitance—act to reduce the characteristic impedance (Z₀) of the transmission line, as defined by the simplified formula Z₀ = √(L/C), where L is inductance and C is capacitance per unit length.

In practical design, this relationship is leveraged to hit target impedance values, such as the common 50Ω or 75Ω standards. For a given dielectric thickness and material, a specific width is calculated to achieve the desired Z₀. However, the reality is nuanced. Manufacturing tolerances mean the etched width can vary from the designed width, directly impacting the final impedance. Furthermore, at very high frequencies, the skin effect confines current to the surface of the trace, making the effective resistance a function of the perimeter rather than the area. This makes consistent width control and surface finish critical for predictable high-frequency performance.

The Critical Influence of Trace Spacing and Coupling

While width governs a trace's relationship with its reference plane, spacing dictates its relationship with neighboring traces. When two traces carrying signals run in parallel over a significant distance, electromagnetic fields interact, leading to capacitive and inductive coupling. This phenomenon, known as crosstalk, can severely degrade signal integrity. The spacing between traces is the primary lever to manage this coupling. Increasing the spacing reduces both the mutual capacitance and mutual inductance, thereby exponentially decreasing crosstalk. A common rule of thumb is to space traces at least three times the dielectric height apart to minimize coupling to acceptable levels.

The spacing also plays a pivotal role in differential pair routing, a cornerstone of high-speed interfaces like USB, PCIe, and HDMI. A differential pair consists of two traces carrying complementary signals. Their impedance is characterized by both the differential impedance (between the two traces) and the common-mode impedance (of each trace to ground). The spacing between the two traces of the pair is a key variable. Tighter spacing increases coupling between the pair, which raises the differential impedance for a given single-ended width. Designers must carefully balance trace width and intra-pair spacing to achieve the target differential impedance (often 100Ω) while maintaining adequate isolation from other signals on the board.

The Dielectric Material: The Silent Enabler

The insulating material, or dielectric, that surrounds and supports the copper traces is not a passive backdrop but an active participant in determining impedance. Its most relevant property is the dielectric constant (Dk or εr), which measures a material's ability to store electrical energy in an electric field. A higher Dk material increases the capacitance between the trace and the ground plane, which, as per the Z₀ formula, lowers the characteristic impedance for a given geometry. Therefore, selecting a PCB substrate material with a stable and well-known Dk is crucial for predictable impedance control.

Beyond the nominal Dk value, real-world material behavior introduces complexity. The Dk can vary with frequency (dispersion), temperature, and even the direction of the electric field in anisotropic materials like woven glass-reinforced laminates. Furthermore, the dielectric thickness (H), or the distance from the trace layer to the reference plane, is a geometric factor of equal importance to trace width. For a microstrip trace (on an outer layer), impedance is inversely proportional to the square root of the effective Dk and is highly sensitive to the ratio of trace width to dielectric height (W/H). A thicker dielectric increases impedance by reducing capacitance. Designers must therefore specify both the material and the controlled dielectric thickness during stack-up design to achieve accurate impedance targets.

Synthesis for Optimal Performance: Tools and Trade-offs

Mastering the individual effects of width, spacing, and dielectric is only the first step. The art of high-performance PCB design lies in synthesizing these parameters under real-world constraints. This synthesis is facilitated by electromagnetic field solvers and impedance calculators, which can model complex scenarios beyond simple microstrip lines, such as stripline (embedded traces), coplanar waveguides, and accounts for solder mask effects. These tools allow designers to iterate quickly, finding a geometry that meets electrical requirements while adhering to manufacturing design rules for minimum width and spacing.

Ultimately, the design process involves navigating key trade-offs. A desire for high routing density pushes for thinner traces and tighter spacing, which can lower impedance and increase crosstalk. Using a material with a higher Dk allows for narrower traces to achieve the same impedance, saving space but potentially introducing greater loss. The choice of stack-up—the arrangement of signal, ground, and power layers—defines the available dielectric heights and reference paths, locking in fundamental geometric constraints. The optimal design is thus a balanced solution that satisfies electrical performance, physical size, manufacturability, and cost, all rooted in a profound understanding of how trace geometry shapes the invisible world of impedance.

REPORT