-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

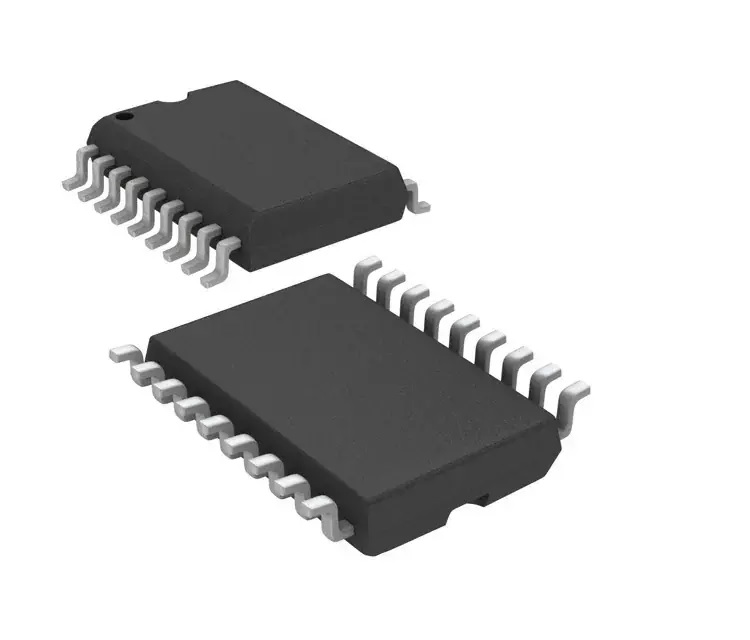

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

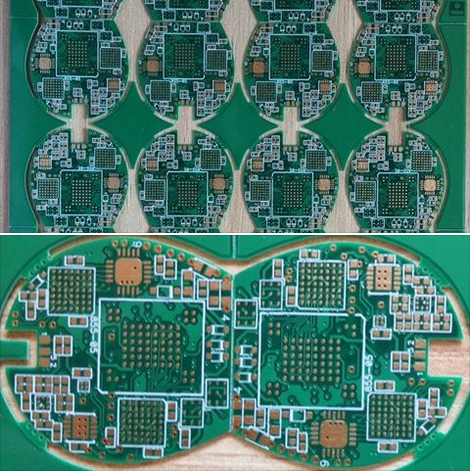

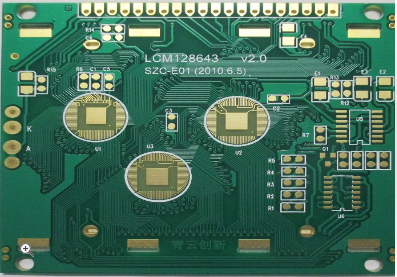

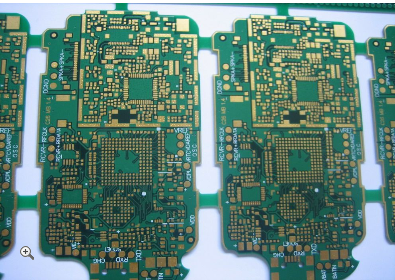

Implementing Design For Manufacturing Guidelines In PCB Layout Projects

In the intricate world of electronics development, the journey from a schematic diagram to a functional, mass-produced printed circuit board (PCB) is fraught with potential pitfalls. While a PCB layout might appear flawless in simulation, its real-world manufacturability ultimately determines project success, cost, and time-to-market. This is where the systematic application of Design for Manufacturing (DFM) guidelines becomes paramount. Implementing DFM in PCB layout projects is not merely a final checklist but a foundational philosophy integrated throughout the design process. It serves as the critical bridge between the theoretical design and the practical realities of fabrication and assembly, ensuring that brilliant ideas are translated into reliable, high-yield, and cost-effective physical products. By proactively addressing manufacturing constraints during layout, engineers can avoid costly re-spins, delays, and quality issues, making DFM an indispensable discipline in modern electronics design.

Fundamental DFM Principles in Component Placement and Footprint Design

The initial stages of PCB layout, particularly component placement and footprint creation, set the stage for manufacturability. Adherence to DFM begins with the library. Each component footprint must be meticulously designed according to the manufacturer's datasheet, ensuring accurate pad sizes, shapes, and spacing. Pads that are too small can lead to poor solder joints, while oversized pads may cause bridging or tombstoning during reflow soldering. Furthermore, incorporating clear silkscreen outlines and polarity markers within the footprint aids assembly technicians and reduces placement errors.

Strategic component placement is equally crucial. A core DFM tenet is orienting similar components in the same direction, typically 0° or 90°, to optimize the pick-and-place machine's movement and speed. Sufficient spacing must be maintained between components to allow for the solder paste stencil aperture, the soldering iron tip for potential rework, and automated optical inspection (AOI) equipment. Special attention is required for large, heavy components like connectors or heatsinks, which may need additional mechanical support or specific placement to prevent warping during soldering or stress during use. By mastering these placement rules, designers create a layout that is not only electrically sound but also optimized for automated assembly lines.

Optimizing Trace Routing and Copper Features for Fabrication Yield

Once components are placed, the routing of traces and definition of copper pours must conform to the capabilities of the PCB fabricator. This involves adhering to a set of minimum design rules dictated by the chosen manufacturer's process. Key parameters include minimum trace width and spacing, which directly impact the board's current-carrying capacity, impedance control, and susceptibility to short circuits. Pushing these limits to the absolute minimum increases cost and reduces fabrication yield; therefore, using wider traces and greater clearances where possible enhances reliability.

Copper balancing is another critical, yet often overlooked, DFM consideration. Large areas of copper on one layer without corresponding copper on opposite layers can cause the board to warp during the high-temperature lamination process. This warpage can lead to registration issues in multilayer boards and problems during assembly. To mitigate this, designers should use hatched copper pours or add thieving—non-connected copper shapes—on sparse layers. Additionally, avoiding acute angles in traces and ensuring adequate annular rings for vias and through-hole pads prevent acid traps during etching and weak mechanical connections, respectively. These practices ensure the bare board is robust and consistently producible.

Incorporating Assembly and Testability Features from the Start

DFM extends beyond fabrication to encompass the entire assembly and test process. A layout must be designed for efficient and error-free population with components. This involves providing adequate clearance around the board edges for handling by conveyor belts in assembly machines and including tooling holes or fiducial markers. Global and local fiducials—precise copper markers—are essential for vision systems on pick-and-place machines to accurately align the board and place components, especially for fine-pitch BGAs or QFNs.

Design for Testability (DFT), a subset of DFM, is integral to ensuring product quality. This means incorporating test points for critical nets to allow for in-circuit testing (ICT) or flying probe testing. These test points must be accessible, properly sized, and located away from tall components. For boards requiring boundary-scan testing, adhering to JTAG chain requirements during layout is vital. Furthermore, considering rework accessibility by avoiding placing large components directly over vias or sensitive areas can save significant time and cost during debugging and repair phases. By designing with assembly and test in mind, the transition from populated board to verified product becomes seamless and efficient.

Leveraging DFM Analysis Tools and Collaboration with Partners

Successfully implementing DFM guidelines is greatly facilitated by modern electronic design automation (EDA) tools. Most advanced PCB layout software includes built-in DFM rule checks that can validate designs against user-defined or manufacturer-supplied rule sets. These automated checks can flag issues like silkscreen over pads, insufficient solder mask slivers, or copper too close to the board edge, which might be tedious to find manually. Running these checks iteratively throughout the design process, rather than just at the end, allows for early correction of potential faults.

However, tools are only as good as the rules they use. The most effective DFM strategy involves early and ongoing collaboration with manufacturing partners. Engaging with your chosen PCB fabricator and assembly house during the design phase allows you to tailor your layout to their specific equipment, processes, and capabilities. They can provide their most up-to-date process capability matrices, recommending optimal values for hole sizes, copper weights, and solder mask expansion. This collaborative approach transforms DFM from a generic set of rules into a targeted, optimized practice, dramatically increasing the likelihood of first-pass success and building a stronger, more predictable supply chain.

REPORT