-

Agriculture

Agriculture

-

Health-Care

Health-Care

-

Environment

Environment

-

Construction-Real-Estate

Construction-Real-Estate

-

Tools-Hardware

Tools-Hardware

-

Home-Garden

Home-Garden

-

Furniture

Furniture

-

Luggage-Bags-Cases

Luggage-Bags-Cases

-

Medical-devices-Supplies

Medical-devices-Supplies

-

Gifts-Crafts

Gifts-Crafts

-

Sports-Entertainment

Sports-Entertainment

-

Food-Beverage

Food-Beverage

-

Vehicles-Transportation

Vehicles-Transportation

-

Power-Transmission

Power-Transmission

-

Material-Handling

Material-Handling

-

Renewable-Energy

Renewable-Energy

-

Safety

Safety

-

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

Testing-Instrument-Equipment

-

Construction-Building-Machinery

Construction-Building-Machinery

-

Pet-Supplies

Pet-Supplies

-

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

Personal-Care-Household-Cleaning

-

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

Vehicle-Accessories-Electronics-Tools

-

School-Office-Supplies

School-Office-Supplies

-

Packaging-Printing

Packaging-Printing

-

Mother-Kids-Toys

Mother-Kids-Toys

-

Business-Services

Business-Services

-

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

Commercial-Equipment-Machinery

-

Apparel-Accessories

Apparel-Accessories

-

Security

Security

-

Shoes-Accessories

Shoes-Accessories

-

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

Vehicle-Parts-Accessories

-

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

Jewelry-Eyewear-Watches-Accessories

-

Lights-Lighting

Lights-Lighting

-

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

Fabric-Textile-Raw-Material

-

Fabrication-Services

Fabrication-Services

-

Industrial-Machinery

Industrial-Machinery

-

Consumer-Electronics

Consumer-Electronics

-

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

Electrical-Equipment-Supplies

-

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

Electronic-Components-Accessories-Telecommunications

-

Home-Appliances

Home-Appliances

-

Beauty

Beauty

-

Chemicals

Chemicals

-

Rubber-Plastics

Rubber-Plastics

-

Metals-Alloys

Metals-Alloys

- Masonry Materials

- Curtain Walls & Accessories

- Earthwork Products

- Fireproofing Materials

- Heat Insulation Materials

- Plastic Building Materials

- Building Boards

- Soundproofing Materials

- Timber

- Waterproofing Materials

- Balustrades & Handrails

- Bathroom & Kitchen

- Flooring & Accessories

- Tiles & Accessories

- Door, Window & Accessories

- Fireplaces & Stoves

- Floor Heating Systems & Parts

- Stairs & Stair Parts

- Ceilings

- Elevators & Escalators

- Stone

- Countertops, Vanity Tops & Table Tops

- Mosaics

- Metal Building Materials

- Multifunctional Materials

- Ladders & Scaffoldings

- Mouldings

- Corner Guards

- Decorative Films

- Formwork

- Building & Industrial Glass

- Other Construction & Real Estate

- Wallpapers/Wall panels

- HVAC System & Parts

- Outdoor Facilities

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Festive & Party Supplies

- Bathroom Products

- Household Sundries

- Rain Gear

- Garden Supplies

- Household Cleaning Tools & Accessories

- Lighters & Smoking Accessories

- Home Storage & Organization

- Household Scales

- Smart Home Improvement

- Home Textiles

- Kitchenware

- Drinkware & Accessories

- Dinnerware, Coffee & Wine

- Home Decor

- Golf

- Fitness & Body Building

- Amusement Park Facilities

- Billiards, Board Game,Coin Operated Games

- Musical Instruments

- Outdoor Affordable Luxury Sports

- Camping & Hiking

- Fishing

- Sports Safety&Rehabilitation

- Ball Sports Equipments

- Water Sports

- Winter Sports

- Luxury Travel Equipments

- Sports Shoes, Bags & Accessories

- Cycling

- Other Sports & Entertainment Products

- Artificial Grass&Sports Flooring&Sports Court Equipment

- Scooters

- Food Ingredients

- Honey & Honey Products

- Snacks

- Nuts & Kernels

- Seafood

- Plant & Animal Oil

- Beverages

- Fruit & Vegetable Products

- Frog & Escargot

- Bean Products

- Egg Products

- Dairy Products

- Seasonings & Condiments

- Canned Food

- Instant Food

- Baked Goods

- Other Food & Beverage

- Meat & Poultry

- Confectionery

- Grain Products

- Feminie Care

- Hair Care & Styling

- Body Care

- Hands & Feet Care

- Hygiene Products

- Men's Grooming

- Laundry Cleaning Supplies

- Travel Size & Gift Sets

- Room Deodorizers

- Other Personal Care Products

- Pest Control Products

- Special Household Cleaning

- Floor Cleaning

- Kitchen & Bathroom Cleaning

- Oral Care

- Bath Supplies

- Yellow Pages

- Correction Supplies

- Office Binding Supplies

- Office Cutting Supplies

- Board Erasers

- Office Adhesives & Tapes

- Education Supplies

- Pencil Cases & Bags

- Notebooks & Writing Pads

- File Folder Accessories

- Calendars

- Writing Accessories

- Commercial Office Supplies

- Pencil Sharpeners

- Pens

- Letter Pad/Paper

- Paper Envelopes

- Desk Organizers

- Pencils

- Markers & Highlighters

- Filing Products

- Art Supplies

- Easels

- Badge Holder & Accessories

- Office Paper

- Printer Supplies

- Book Covers

- Other Office & School Supplies

- Stationery Set

- Boards

- Clipboards

- Stamps

- Drafting Supplies

- Stencils

- Electronic Dictionary

- Books

- Map

- Magazines

- Calculators

- Baby & Toddler Toys

- Educational Toys

- Classic Toys

- Dress Up & Pretend Play

- Toy Vehicle

- Stuffed Animals & Plush Toys

- Outdoor Toys & Structures

- Balloons & Accessories

- Baby Food

- Children's Clothing

- Baby Supplies & Products

- Maternity Clothes

- Kids Shoes

- Baby Care

- Novelty & Gag Toys

- Dolls & Accessories

- Puzzle & Games

- Blocks & Model Building Toys

- Toddler Clothing

- Baby Clothing

- Kids' Luggage & Bags

- Arts, Crafts & DIY Toys

- Action & Toy Figures

- Baby Appliances

- Hobbies & Models

- Remote Control Toys

- Promotional Toys

- Pregnancy & Maternity

- Hygiene Products

- Kid's Textile&Bedding

- Novelty & Special Use

- Toy Weapons

- Baby Gifts

- Baby Storage & Organization

- Auto Drive Systems

- ATV/UTV Parts & Accessories

- Marine Parts & Accessories

- Other Auto Parts

- Trailer Parts & Accessories

- Auto Transmission Systems

- Train Parts & Accessories

- Universal Parts

- Railway Parts & Accessories

- Auto Brake Systems

- Aviation Parts & Accessories

- Truck Parts & Accessories

- Auto Suspension Systems

- Auto Lighting Systems

- New Energy Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Steering Systems

- Wheels, Tires & Accessories

- Bus Parts & Accessories

- Auto Performance Parts

- Cooling System

- Go-Kart & Kart Racer Parts & Accessories

- Air Conditioning Systems

- Heavy Duty Vehicle Parts & Accessories

- Auto Electrical Systems

- Auto Body Systems

- Auto Engine Systems

- Container Parts & Accessories

- Motorcycle Parts & Accessories

- Refrigeration & Heat Exchange Equipment

- Machine Tool Equipment

- Food & Beverage Machinery

- Agricultural Machinery & Equipment

- Apparel & Textile Machinery

- Chemical Machinery

- Packaging Machines

- Paper Production Machinery

- Plastic & Rubber Processing Machinery

- Industrial Robots

- Electronic Products Machinery

- Metal & Metallurgy Machinery

- Woodworking Machinery

- Home Product Manufacturing Machinery

- Machinery Accessories

- Environmental Machinery

- Machinery Service

- Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Machinery

- Industrial Compressors & Parts

- Tobacco & Cigarette Machinery

- Production Line

- Used Industrial Machinery

- Electronics Production Machinery

- Other Machinery & Industrial Equipment

- Camera, Photo & Accessories

- Portable Audio, Video & Accessories

- Television, Home Audio, Video & Accessories

- Video Games & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Accessories

- Electronic Publications

- Earphone & Headphone & Accessories

- Speakers & Accessories

- Smart Electronics

- TV Receivers & Accessories

- Mobile Phone & Computer Repair Parts

- Chargers, Batteries & Power Supplies

- Used Electronics

- VR, AR, MR Hardware & Software

- Projectors & Presentation Equipments

- Other Consumer Electronics

- Cables & Commonly Used Accessories

- Computer Hardware & Software

- Displays, Signage and Optoelectronics

- Discrete Semiconductors

- Wireless & IoT Module and Products

- Telecommunications

- Connectors, Terminals & Accessories

- Development Boards, Electronic Modules and Kits

- Circuit Protection

- Sensors

- Isolators

- Audio Components and Products

- Integrated Circuits

- Power Supplies

- Relays

- RF, Microwave and RFID

- Electronic Accessories & Supplies

- Passive Components

- PCB & PCBA

- Air Quality Appliances

- Home Appliance Parts

- Heating & Cooling Appliances

- Small Kitchen Appliances

- Laundry Appliances

- Water Heaters

- Water Treatment Appliances

- Refrigerators & Freezers

- Personal Care & Beauty Appliances

- Major Kitchen Appliances

- Cleaning Appliances

- Second-hand Appliances

- Smart Home Appliances

- Other Home Appliances

- Energy Chemicals

- Inorganic Chemicals

- Basic Organic Chemicals

- Agrochemicals

- Admixture & Additives

- Catalysts & Chemical Auxiliary Agents

- Pigments & Dyestuff

- Coating & Paint

- Daily Chemicals

- Polymer

- Organic Intermediate

- Adhesives & Sealants

- Chemical Waste

- Biological Chemical Products

- Surface Treatment Chemicals

- Painting & Coating

- Chemical Reagents

- Flavor & Fragrance

- Non-Explosive Demolition Agents

- Other Chemicals

- Custom Chemical Services

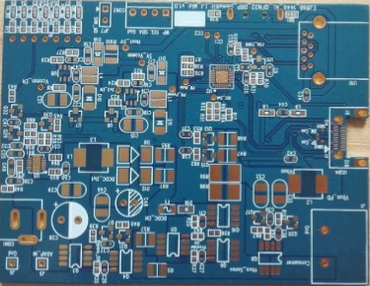

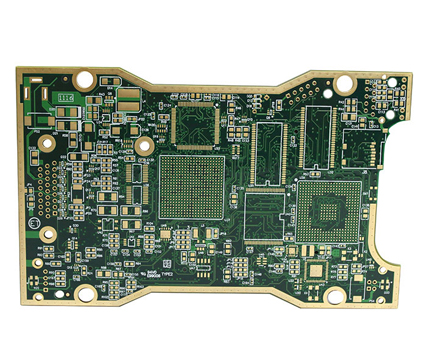

Understanding Impedance Control in PCB Design Key Factors for Signal Integrity and High Speed Performance Across Various Applications

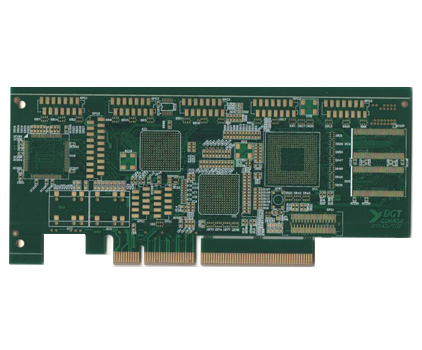

In the rapidly evolving landscape of electronics, where devices are becoming faster, smaller, and more interconnected, the integrity of the signals traveling within them is paramount. At the heart of this challenge lies the printed circuit board (PCB), the foundational platform that hosts and interconnects all electronic components. For decades, PCB design was primarily concerned with correct connectivity and power distribution. However, with the advent of high-speed digital interfaces, RF communications, and high-frequency computing, a new critical discipline has emerged: controlled impedance. Understanding impedance control in PCB design is no longer a niche concern for radio frequency engineers; it is a fundamental requirement for ensuring signal integrity and achieving reliable high-speed performance across a vast array of applications, from consumer smartphones and data centers to automotive radar and medical imaging systems. This article delves into the key factors that govern impedance control, exploring why it matters and how mastering it is essential for the functionality of modern electronics.

The Fundamental Principles of Impedance and Its Critical Role

Impedance, in the context of a PCB trace, is the measure of opposition that the trace presents to the flow of alternating current (AC). Unlike simple DC resistance, impedance is a complex quantity that encompasses both resistance and reactance (the opposition from capacitance and inductance). For high-speed signals, which are essentially AC waveforms, the characteristic impedance of a transmission line (the PCB trace and its reference plane) must be carefully controlled and matched throughout the signal's path.

When the impedance is not uniform—for instance, when a trace of one impedance connects to a component with a different input impedance—a phenomenon called signal reflection occurs. Part of the signal energy bounces back towards the source, interfering with the original signal. This leads to a host of signal integrity issues, including ringing, overshoot, undershoot, and increased settling times. In digital systems, these distortions can corrupt data, cause timing errors (jitter), and ultimately lead to system failures. Therefore, the primary goal of impedance control is to create a consistent transmission line environment that minimizes reflections, preserves signal shape, and ensures that the maximum power is delivered from the driver to the receiver.

Key Design Factors Governing Controlled Impedance

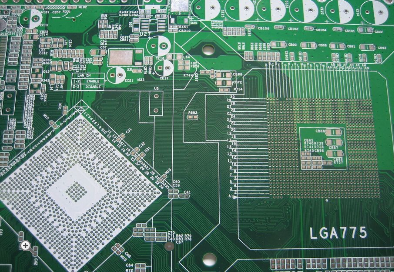

Achieving a target characteristic impedance (common values are 50Ω for single-ended and 100Ω for differential pairs) is a precise engineering task dictated by several interrelated physical parameters of the PCB stack-up. The trace width is a primary variable; a wider trace lowers the impedance, while a narrower trace increases it. This relationship is directly influenced by the dielectric material separating the trace from its reference plane, typically a ground or power plane.

The thickness of this dielectric core or prepreg material, known as the dielectric height (H), is equally crucial. A greater distance between the trace and the plane increases the impedance. Furthermore, the properties of the dielectric material itself, specifically its dielectric constant (Dk or εr), play a major role. Materials with a lower Dk, such as specialized high-speed laminates like Rogers or Isola FR408HR, are preferred for high-frequency designs as they allow for faster signal propagation and offer more stable electrical properties across a range of frequencies. Finally, the thickness of the copper trace (T) also has a minor effect. These factors are mathematically related through established formulas and are managed using industry-standard field solvers within PCB design software to simulate and calculate the required dimensions before manufacturing.

Impedance Control Across Different PCB Structures

Not all transmission lines on a PCB are created equal, and the approach to impedance control varies with the physical structure. The most common configuration is the microstrip, where a trace is routed on an external layer with a single reference plane below it. Its impedance is relatively straightforward to calculate but can be affected by surface finishes and solder mask. For internal layers, the stripline configuration is used, where a trace is embedded between two reference planes. This offers excellent shielding and noise immunity but requires careful consideration of both dielectric layers above and below the trace.

For critical high-speed differential signaling, such as PCI Express, USB, or HDMI, pairs of traces are routed together. Here, the goal is to control both the differential impedance (between the two traces) and the common-mode impedance (of each trace to ground). This requires precise control over the trace width, the spacing between the two traces, and their coupling to the reference plane. As signal speeds push into the multi-gigabit range, even more advanced considerations like broadside-coupled striplines or variations in coplanar waveguide designs may be employed to manage crosstalk and electromagnetic interference (EMI) more effectively.

The Critical Link to Manufacturing and Testing

Impedance control is a partnership between design and fabrication. The designer's calculations and stack-up definitions are only as good as the manufacturer's ability to realize them. Tolerances in material thickness, dielectric constant, and copper etching can all cause the final impedance to deviate from the target. Therefore, clear communication via detailed fabrication notes and impedance control tables is essential. These documents specify the target impedance, the trace geometry, the associated layer, and the acceptable tolerance (typically ±10%).

Verification is the final, indispensable step. Post-manufacturing, PCB fabricators use time-domain reflectometry (TDR) testers to measure the actual characteristic impedance of production samples. A TDR sends a fast step signal down a test trace and analyzes the reflections to precisely determine the impedance profile along its length. This testing validates that the manufactured board meets the specified requirements before it is populated with expensive components, preventing costly failures later in the assembly process.

Application-Specific Considerations and Future Trends

The necessity for impedance control spans the entire spectrum of modern electronics. In telecommunications and networking equipment, it ensures the fidelity of high-speed serial data links. In computing, it is vital for memory interfaces (DDR4/5) and processor buses. Automotive applications, particularly Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) relying on radar and high-speed cameras, demand rigorous impedance control for accurate sensor data. Even consumer devices, with their compact form factors and mixed-signal designs, require careful impedance management to prevent digital noise from interfering with sensitive RF or analog circuits.

Looking ahead, the push for higher data rates, lower power consumption, and increased integration will only intensify the focus on impedance control. Technologies like silicon interposers and advanced packaging (e.g., fan-out wafer-level packaging) are bringing transmission line challenges into the package substrate itself. Furthermore, the adoption of higher-frequency bands for 5G/6G and the rise of millimeter-wave applications will necessitate even tighter tolerances, the use of ultra-low-loss materials, and sophisticated 3D electromagnetic modeling to account for effects like surface roughness and dielectric loss tangent, ensuring signal integrity remains robust in the next generation of electronic design.

REPORT